The arrival of new rail lines in the late 1800s connected the Treasure Valley, allowing Boise residents greater mobility. Completion of the Boise Interurban Transportation System in 1917 provided greater access to the bench and spurred the advancement of the Central Rim Neighborhood. As the neighborhood grew, new challenges emerged, reflecting a changing society. The Central Rim community identity evolved with transportation and development to depict a cross section of Boise’s development.[1]

Special Thanks: Carol Long Cooper.

The Central Rim remained rural land with only small-scale improvements until the arrival of the Oregon Short Line in 1893 and the installment of the Interurban Transportation System. Railways opened the area to residents who were looking for a quiet rural home next to the city, creating Boise’s first suburbs. Initially the community emerged around a setting that incorporated rural life with urban access. By 1917 residents enjoyed the artistic and economic benefits of having four rail lines in the neighborhood. Riding the “Boise Loop” became a popular activity for residents, who for a dollar could ride the complete loop from downtown to Caldwell and enjoy the convenience of getting off near their home. As the automobile began to emerge, Boise removed the Interurban System in 1928 and the Central Rim neighborhood lost a piece of its early identity. Although the neighborhood would continue to evolve under the automobile, a largely rural setting would remain well into middle of the twentieth century.[2]

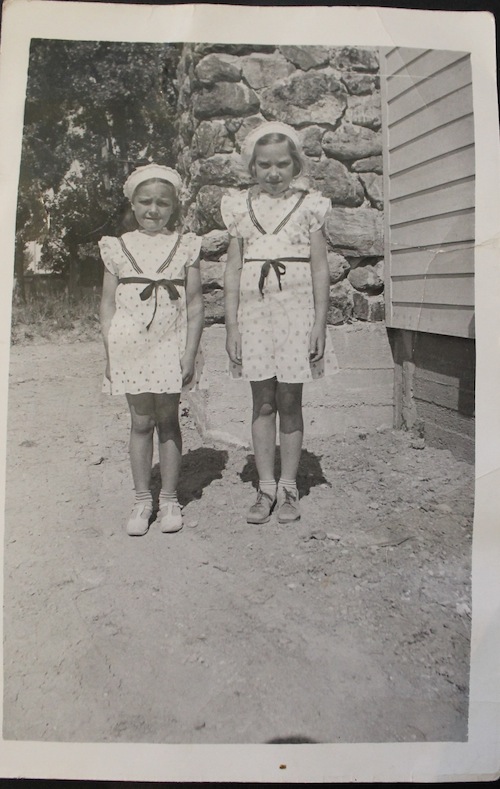

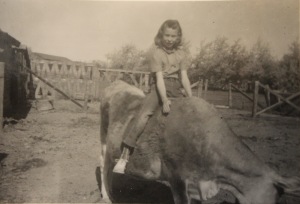

Lifelong residents Pat Schubert and Carol Long provide insight into the lifestyle of Central Rim youth. The rural environment of the neighborhood shaped the lives of the children who grew up there. Carol Long describes her childhood, “My friends and I were in a riding club called The Copper Riding Club and we would practice at the Fairgrounds.” While this rural setting remained through postwar development, population increase led to the renaming of streets. Describing annexation, Pat recalls, “We had a route number and then after annexation our address was 1004 N. Garden.” Residents enjoyed the presence of the state fair, which until 1968 remained located near the Central Rim on land that today houses Idaho Public Television at the corner of Fairview and Orchard. Orchard and Fairview are symbolic avenues: Orchard Street once paralleled the neighborhood’s farmland; Fairview passed along the site that for decades hosted the state fair. Today these streets embody an urban automotive landscape that has replaced the once rustic neighborhood.[3]

Image Courtesy: Carol Long Cooper.

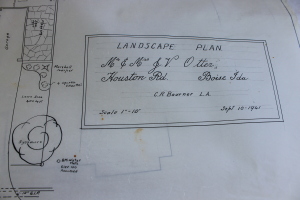

Boise’s growing population included influential members of the city living in the Central Rim. John Vernon Otter, a prominent engineer, constructed his home at 906 Houston Street to oversee the development of Ann Morrison Park. The Otters held their housewarming party on December 7, 1941, a day signaling a change in the path of Boise and the nation. Postwar Boise icons such as the Albertson family joined Joelle Busey and others in continuing the tradition of prominence on Houston Street. These residents built large-scale individually designed homes which showcased Idaho’s growing prosperity and the ideals prominent during mid-twentieth century American life. Joelle Busey, a longtime resident of the community, described moving to the neighborhood, “We moved here because it was an older established neighborhood. There was a mixture of young families, older families, and well-established families.” Mrs. Busey’s neighbors included writer Glen Balsch and Nat Adams, who designed Albertson’s Stadium. Boise’s gradual expansion included the creation of Ann Morrison Park and the full integration of the Central Rim neighborhood in 1963.[4]

Photo Courtesy: Joelle Busey

Images from mid-twentieth century Boise portray a thriving community possessing character and energy flowing from residents. Mrs. Busey recalls the close-knit community that first attracted her: “We watched a lot of football at neighborhood gatherings, and this was when BSU was just becoming a four year university.” The story of Houston Street continues today. Mickey and Gloria Myhre now live in John Vernon Otter’s house. Their home overlooks downtown, the foothills, and both Anne Morrison and Kathryn Albertson parks. The Myhres describe the community and purchase of their home fondly, “We love it here. We were very lucky to acquire this property. Primarily the Albertson family wanted to buy it because Joe Albertson’s house was then two doors down and he had purchased the house next door and across the street. Lucky for us the Otters wanted to sell the property to a young family.” The neighborhood boasts a strong history of community and growth.[5]

Boise began to change in the 1980s and 90s, bringing with it the Connector and a new story of transportation and the Central Rim. The arrival of the Connector, a thoroughfare connecting downtown Boise to Intersate-84, in 1992 completed the city infrastructure’s transformation from rail car to automobile. This transformation had been slowly taking place since 1928, with the demise of the electric rail cars. The connector follows the old Oregon Short Line, once part of the Interurban System, and connects downtown Boise to the outer suburbs and rural communities in much the same way rail cars did before. Today’s residents of the Central Rim enjoy many of the same conveniences as early residents. Mickey Myhre highlighted the transportation advantages of the community, noting, “We’re ten minutes from the airport, a mile from downtown, and we have a great view.” The former presence of rail cars and rural fields seems almost unimaginable in an area impacted by automobiles. The switch from a rural to an urban automotive landscape reflects the broader shift that occurred in America during the twentieth century. However, the steel symbols of a past era remain visible through the Fairview Bridge and the remaining tracks connecting to the Boise Depot. The Fairview Pedestrian Bridge now serves the community by allowing Central Rim residents to walk and bike downtown as easily as they once rode a train.[6]

Special Thanks: Gloria and Mickey Myhre.

Changes in space and its use can provide a community with new opportunities and experiences once unavailable. Change inevitably though cannot all be good, and the Central Rim today experiences growing pains brought on by the processes that helped to develop one of Boise’s most historic neighborhoods. Water has been, and remains, key to the success of the Central Rim. Providing all residents of the neighborhood equal access to water for irrigation has proven a challenge and will require the cooperation of individuals in this close-knit community. The Central Rim community has faced challenges throughout its history and responded with success. Understanding these changes and their effects enables the community to continue developing with sustainability.

Special Thanks: Gloria and Mickey Myhre.

The Central Rim provides a historical and cultural cross section of Boise’s development throughout the twentieth century. The area provided early residents access to rural homes in an urbanizing city via the Interurban System. The community’s early successes and development occurred alongside an emerging city transit system, ultimately attracting families to one of the city’s first suburbs. The mid twentieth century witnessed the emergence of an urban automotive environment in America. The Central Rim once thrived from rail car access; by the completion of annexation, the neighborhood had evolved to represent the impact of the automobile.

Throughout the evolution of the neighborhood, the idea of community has remained durable. Although recent growth and economic trends in the valley have created new obstacles, the community remains a cross section depicting the city’s larger developmental trends. Boise’s Central Rim provides a history dating back to the late 1800s, possessing vibrant characters like Joe Albertson and others who fostered the neighborhood’s symbolic Houston Street. Many others with their own visions and abilities contributed to the progression of the Central Rim from a collection of rural settlers to a historically significant, interconnected community. The development of transportation directly impacted the Central Rim throughout the decades of growth, recession, and urban sprawl. The narrative of the Central Rim community coincides with mobility in the greater Treasure Valley and continuous transformation of space.

Citations:

[1] Thornton Waite, “Boise: On the Main Line At Last,” The Streamliner 11, no. 6, 10, 1-3.

[2] “The Old Overland Route,” Boise Parks & Recreation. September 14, 2012. Accessed October 23, 2014. <http://parks.cityofboise.org/media/6670/unionpacificoldoverlandroute.pdf>.

[3] Schubert, Pat. Personal Interview by Martinez, Alex, Nick Horton, and Adam Behrman. 4511 West Holmes Street. October 10 2014 4:00 PM.

[4] Busey, Joelle. Personal Interview by Behrman, Adam, Rachael Rank, and Brittany Reichel. 1833 Old Saybrook Lane. October 10, 2014. 1:00 PM.

[5] Busey, Joelle. Personal Interview by Behrman, Adam, Rachael Rank, and Brittany Reichel. 1833 Old Saybrook Lane. October 10, 2014. 1:00 PM.

[6] Myhre, Gloria and Mickey. Personal Interview by Behrman, Adam, Rachael Renk, and Brittany Reichel. October 10, 2014. 2:30 PM.

Image Citations:

All images used on this site are copyright the Central Rim Neighborhood Project unless otherwise attributed.

The images featured in this essay were taken by Adam Behrman, Rachael Renk, and Brittany Reichel while conducting interviews with residents of the Central Rim Neighborhood. A special thank you to those interviewed who allowed us to photograph these materials.

Behrman, Adam, Rachael Renk, and Brittany Reichel. Gloria and Mickey Myhre’s Backyard View. Photograph, 2014.

Busey, Joelle. Neighborhood Fun. Photograph, c.1970s.

Long Cooper, Carol. Carol Long, Copper Riding Club. Photograph, n.d.

———. Map of Central Rim Neighborhood’s Original Land Plots. Photograph, 2014.

Myhre, Gloria and Mickey. John Vernon Otter’s Original Landscape Plan. Photograph, n.d.