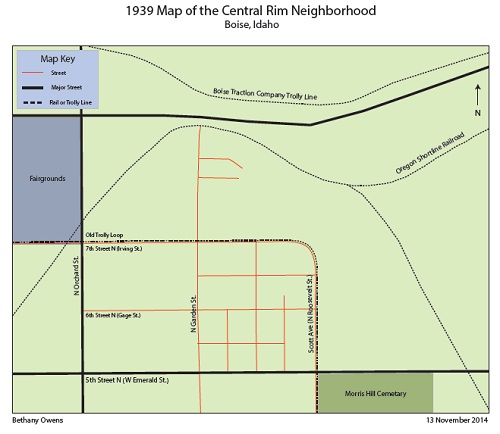

Water played a crucial role in the development and settlement of the Central Rim neighborhood and the Bench region of Boise, Idaho. Boise does not enjoy the abundant precipitation of the Eastern and Midwestern U.S. Early settlers needed ingenuity to make a living; they had to divert water to their land but leave enough for others. They dug canals to distribute water to parched land.

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, Congress passed several pieces of legislation in attempts to direct water to Idaho’s newly agricultural land. The two most notable ones were the Carey Act of 1894, also known as the Desert Land Act of 1894, and the Boise Water Project.The Carey Act gave the President the right to grant up to one million acres of arid desert land to state reclamation offices for irrigating and farming. Idaho was the most successful state developed under this initiative, with 60% of national Carey Act lands being in Idaho. [1]

Image Courtesy: Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-97347.

The Central Rim and Bench area indirectly benefited from the development of the Boise Water Project. According to Mr. Daren Coon, Secretary-Treasurer of the Nampa & Meridian Irrigation District, the Central Rim benefited from the project “because of the increase of availability of water and the change of delivery systems.”[2] The majority of the Central Rim only has river rights, not storage rights.The increase of available water ensured that Bench lands would receive enough water to sustain agricultural development.[3]

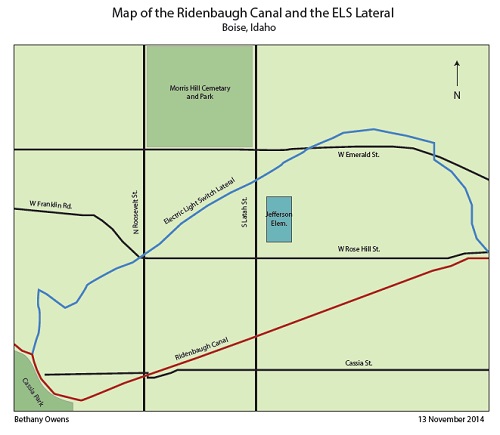

The Ridenbaugh Canal carries vast quantities of water to the Treasure Valley, including the inhabitants of the Central Rim Neighborhood. H.P. and J.C. Isaac dug the ditch, which became the headwaters and release gate for the Ridenbaugh Canal, in 1865. The Ridenbaugh as we know it today was a project originally started by William B. Morris in 1877, and taken up by his nephew after his untimely death.[4]

It was extremely difficult for farmers and ranchers to get irrigation water to their plots. During the tumultuous times of the late 1800s and early 1900s, the Ridenbaugh Canal had many owners, most notably the Central Canal and Land Company and the Boise City Irrigation Land and Lumber Company. When, in 1906, the maintenance for the canal became too great for the various owners it was finally sold to its current owners, the Nampa and Meridian Irrigation District.[5] The Ridenbaugh is the source of the water for several laterals and water reservoirs in the bench region of Boise, ID, including the Central Rim neighborhood.

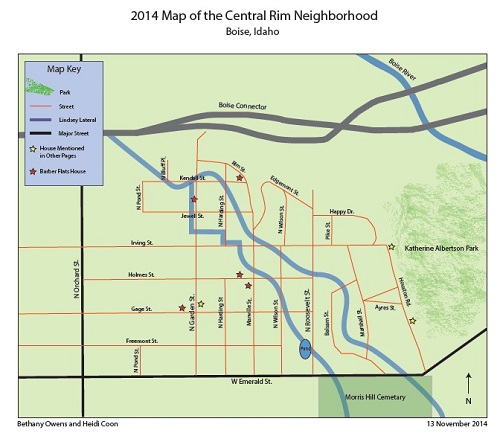

After irrigation became available, the Central Rim consisted of farms, ranches, and orchards. One prominent citizen, M.F. Eby, was known for his prunes and apples—he even won an award at the Omaha State Fair. Mr. Scott, another prominent citizen of the Bench, owned a ranch with assorted animals (pigs, horses, chickens). Many other much smaller farms also relied on irrigation. They received irrigation from the Ridenbaugh Canal, from the Electric Light Switch Lateral and the Scotts Ranch Lateral, known today as the Lindsey Lateral.[6]

As Boise grew, developers subdivided the farms, ranches, and orchards, and the land began yielding houses. The land use may have shifted but the irrigation was, and remains, an integral part of the Central Rim. The water is still used for rearing livestock, like chickens, and irrigates small gardens and lawns.

The Lindsey Lateral Association allocates the majority of the Central Rim’s water to residents. Idaho Statutes requires that if more than two people take water from the same lateral, canal, and or reservoir then they “constitute a water users’ association.”[7] The association is responsible for maintenance, collection of money, and managing the water that runs through the lateral.

The property supplied by the Lindsey Lateral is made up of both tax roll and rental roll. If property falls within the tax roll, the land has a water right and is located in the Irrigation District’s land. If the land is rental roll land then the land has a water right, but the land is not in the District’s boundaries and is not part of the District. When taxes become delinquent, the District will seize the tax deed for non-payment and the property is sold. Water rights cannot be taken from the lands but the lands can be taken away from the property owners. If a rental roll becomes delinquent, the land is not taken from the property for nonpayment; the “water right” is suspended. The suspension of water right is not permanent; however, for it to be reinstated to the land, the property owner has to gain permission from the Irrigation District.[8]

The presence of two different water rights may hinder the neighborhood from gaining pressurized irrigation. There are some lands outside of the Nampa & Meridian Irrigation District and the law does not allow an irrigation district to participate in LIDs (Local Improvement District) outside of the district. Landowners can go through the City of Boise, but because the Boise City Council is a political entity, they have to deal with political pressures. The third option open to water users is to install the system themselves; however, a pressurized irrigation system is very expensive to install. The expenses are from legal and installation costs. Areas of the Central Rim have a pressurized irrigation system supplied through United Water Idaho; however the water is potable drinking water, which is expensive, and depletes the ground water aquifer.[9]

Recently there has been a focus in the neighborhood on water rights. Mickey and Gloria Myhre, who have paid quite a lot for water for their two gorgeous trees on their property, have asked around at city hall and other offices and been dismissed or not told what exactly the water rights entail in plain detail. Ms. Busey as well, when she lived there in the 70s, had always paid for irrigation, but her house wasn’t connected to any canals or ditches. She and her husband always bickered about having to pay the $10 for something they didn’t even use. This is still an issue in this community today. The situation is complicated, no one quite knows who has water rights and who doesn’t.[10]

The Central Rim is currently plagued by flooding and water flow reduction. There are a variety of different reasons that flooding or flow reduction can accrue. Mostly this happens from neglect of the ditches, and construction. Individuals are responsible for the small ditches or buried pipe that go through their property.

Residents may not understand that they are responsible for maintaining the ditch, may not care, cannot afford to, or are physically unable to maintain an open ditch. In the case of a buried pipe many property owners are unaware of their existence.

The best way to deal with flooding and reduced water flow is to handle it before it happens, but this in itself becomes a problem. If a pipe or small ditch is on an individual’s property, it is her responsibility for upkeep even if she doesn’t receive water from it. Neighbors can reach an agreement and offer to help pay to repair the ditch or pipe, but it can become complicated when no one wants to pay for any kind of repair or if there are extenuating circumstances.

One example of extenuating circumstances is the beautiful trees that grow in the Central Rim area. The biggest and tallest are located next to or in the small ditches and their roots can wreak havoc on an irrigation system. The roots block water delivery and the trees use water, which reduces the amount of water to people further down the ditch. This situation becomes tricky because many property owners are not likely to want to take down the trees, and the ditch usually can’t be moved. Consequently, the flooding and water flow decrease reoccurs and the last resort is litigation, which can prove costly and time consuming. Constructing on or filling in of ditches has also become a steadily progressing problem. For example, in 1982, to make room for more parking, a church in the Central Rim paved over a ditch and consequently prevented properties downstream from getting any water.[11]

Similar issues occur today either from an honest misunderstanding or developers who really don’t care how their new buildings may affect others downstream. It has turned a natural resource into a point of contention among neighbors, government, associations, and developers. This neighborhood is too beautiful and historically important to let the misunderstandings and contention destroy its heritage.

Citations:

[1] Petrich, Christian, Margie Wilkins, Tondee Clark, and Tony Morse. “Canals & Irrigation.” Idaho Museum of Natural History. Idaho State University, n.d. Web. <http://imnh.isu.edu/digitalatlas/hydr/cnlsirr/cnlfr.htm>.

[2] Personal Interview with Daren Coon, Secretary-Treasurer, Nampa & Meridian Irrigation District. November 1, 2014

[3] Coon, D. (2014). Daren Coon Interview.

[4] “Ridenbaugh-Rossi Mill Ditch.” Idaho State Historical Society Reference Series. Boise, ID: n.p., 1974. Idaho State Historical Society. Web. 09 Dec. 2014. <http://www.history.idaho.gov/sites/default/files/uploads/reference-series/0515.pdf>.

[5] “Ridenbaugh-Rossi Mill Ditch.” Idaho State Historical Society Reference Series. Boise, ID: n.p., 1974. Idaho State Historical Society. Web. 09 Dec. 2014. <http://www.history.idaho.gov/sites/default/files/uploads/reference-series/0515.pdf>.

[6] “Medals Secured by the State of Omaha,” Idaho Daily Statesman, November 19, 1898, pg 6. “War with a Railroad,” Idaho Daily Statesman, May 28, 1893, pg 8.

[7] Idaho Code 42-1301 for more information. <http://legislature.idaho.gov/idstat/Title42/T42CH13SECT42-1301.htm>.

[8] Coon, D. (2014). Daren Coon Interview.

[9] Coon, D. (2014). Daren Coon Interview.

[10] Brittany Reichel’s reflections on an interview with neighborhood residents. Interview with Mickey and Gloria Myhre, Residents of the Central Rim neighborhood, Boise, ID, Interviewee Brittany Reichel, October 10, 2014.

[11] Albert H. Tennyson to Joseph C. Voight, 9 July 1982

Image Citations:

All images used on this site are copyright the Central Rim Neighborhood Project unless otherwise attributed.

Fair & Thompson. Bird’s-Eye View of Farmland and Mountain, with Orchard in Foreground, Lewiston Valley, Idaho] / Fair & Thompson, Lewiston, Idaho. Photograph, c. 1904. Library of Congress. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/89711646/.

Harris & Ewing. RECLAMATION, BUREAU OF. ARROWCOCK DAM, BOISE, IDAHO, SHOWING TUNNEL WHICH CARRIES BOISE RIVER DURING CONSTRUCTION. Photograph, 1912. Library of Congress. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/hec2008002492/.